I joined Chicago Graduate School of Business, as it was known at that time, in 1987. I thought that I knew a lot about finance, having done my MCom from HR College and qualified as a chartered accountant. So, against the advice of many well-wishers, I signed up to take Gene Fama’s two-quarter course in my very first quarter at Chicago. And I entered the perfect storm. The course was intense and I struggled to stay above water for most of those two quarters. That was my rude introduction to finance at Chicago. Fama was a great professor and was brutal at the same time. But he also had a great sense of humour and was extremely passionate about his work.

I remember one incident very clearly. On Black Monday (19 October 1987) the Dow Jones Industrial Average fell 508 points, dropping 22% that day. This was the biggest drop ever and we had Fama’s class that afternoon. He walked into class and said that a reporter had just called him for his views on why the markets had crashed. Fama told him, half in jest, “I look at historical data… I’ll tell you after five years”. And that was his hallmark—his life’s work revolved on analysing data.

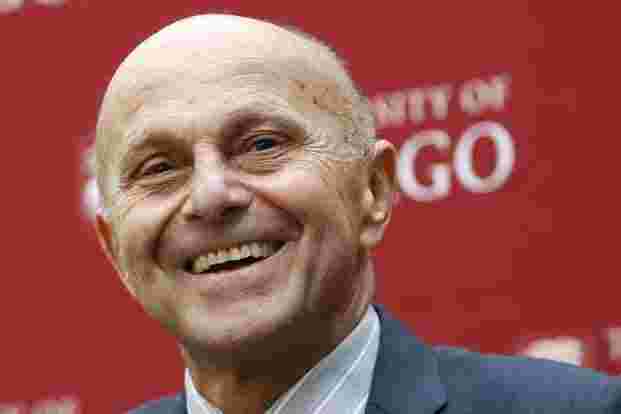

Fama celebrates 50 years at Chicago Booth this year, together with another great professor, Harry Davis (who has been my mentor for the past 25 years and who played a tremendous role in changing the way leadership is taught at business schools across the world). Earlier today, I received the latest copy of the Chicago Booth Magazine, which is dedicated to these two great legends. To borrow from the magazine: “Fama, the consummate researcher in his 50 years at Booth, changed the way generations look at the stock market. His rigorous standards have elevated the work of students and colleagues.” The article goes on to talk about how his dissertation, The Behaviour of Stock Market Prices, followed by Efficient Capital Markets: A review of Theory and Empirical Work, revolutionized the understanding of financial markets.

Fama got tenured at the young age of 26! About a year ago, Fortune magazine ran an article on the best advice financial wizards had received. Fama talked about what another Chicago Booth professor, Harry Roberts, told him: “Harry always said that your criterion should be not whether or not you can reject or accept the hypothesis, but what you can learn from the data.” Fama’s work has always been empirical and he was one of the first academics to use computers.

His work on efficient markets inspired David Booth, who set up Dimensional Fund Advisors, to put Fama’s work into practice. A few years ago, David Booth donated $300 million to the school and Chicago GSB had a new name, Chicago Booth.

Fama’s work on market efficiency has been criticized a lot over the years, especially whenever there is a financial crisis, and people say that markets are inefficient. And this is because people do not understand what Fama says. “Efficient markets” does not mean that the market will always be correct. What efficiency means is that the markets aggregate the information that people have and reflect it quickly into asset prices.

Many of us thought that Fama had lost the chance to win the Nobel Prize since he did not get it when other efficient markets guys won it over a decade ago and the world loves talking today about market inefficiency. I just called my close friend, Bruce Rigal, who is one of the few guys I know who got an “A” in Fama’s class, to tell him that he can now say that he was taught by a Nobel laureate.

Today’s news highlights one of the reasons why I am very passionate about my Chicago Booth experience. I had the chance to be taught by two Nobel Prize winners—Fama and George Stigler (who won his prize in 1982). Stigler is best known for his work on regulatory capture—how special interest groups use regulations to benefit themselves. And I also got a chance to debate on a panel with another Nobel Prize winner, Gary Becker. So what if one of them thought I was incompetent!

Luis Miranda spent most of his post-Chicago Booth life in the less traumatic world of finance. He was a part of the start-up team at HDFC Bank and founded IDFC Private Equity. Luis now spends most of his time, together with his wife Fiona, in the social sector with organizations such as Centre for Civil Society, SNEHA and Samhita.