Soon after he resigned as the chief executive of IDFC Private Equity, Luis Miranda decided to climb the 5,895-metre Mt Kilimanjaro, Africa’s tallest mountain, with his son, who was then 13.

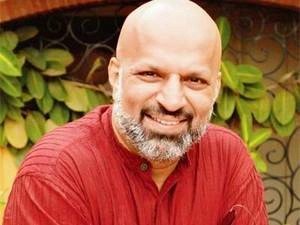

A workaholic for two decades—colleagues were accustomed to 4 am emails from him—Miranda was stepping off this non-stop treadmill, and stepping away from the limelight at just 48 to spend time with his family.

The man who worked with Citibank and HSBC, and was part of the founding team of HDFC, was taking his career in an all new direction—as a philanthropist. For the last two years, Miranda has been using some skills learnt as a PE fund manager to retool non-profits , and extract money and support from hesitant high net worth donors.

Rather than get tied down to one organisation, Miranda has recast himself as something of a philanthropic catalyst , using his powers of persuasion and strong business network to advocate the cause of a bunch of organisations.

Also read: Redrawing the education system

Guide And Catalyst

Despite juggling part-time roles at so many outfits, Miranda of 2012 is in sharp contrast to the fund manager or banker three or more years ago. Bright-coloured kurtas have replaced western formals .

A relentless work life, replete with late-night and early-morning emails and calls, has given way to mountain climbs, active involvement in his 17-year old daughter’s school activities and the occasional afternoon nap.

The biggest change for 50-year old Miranda is stepping back from being a hands-on fund head to being more of a guide and catalyst, connecting causes with donors and pushing more of his peers to give both their money and time to the forums he supports. It is just this combination that attracted Sneha’s founder Armida Fernandez to snap up Miranda as an advisor.

In the 18 months since, he’s overhauled a rickety organisation with a noble cause (improving child and women nutrition) into a professionally run outfit . “Miranda has the exterior of a corporate executive and the heart of a social-sector worker,” she says. Miranda has overhauled Sneha’s reporting structure, pushed board members to play a more active role in the organisation’s functioning and helped raise around Rs 5 crore for its two programmes—nutrition and maternal health.

“He’s also helped better present our finances to investors , and his name and brand have also put a foot in the door during fund-raising ,” says Fernandez.

Twenty Years On

Making a difference has been a long-running desire in Miranda’s mind. Even when he was beginning his career, he thought about becoming a politician, “but it requires a different skill set” . Instead, he worked his way through banks such as HSBC and HDFC, and then to ChrysCapital before becoming the chief executive of IDFC PE in 2002.

“I considered retiring… the challenge of being in infrastructure financing and proving myself had faded,” he says. “There was a lot of money being thrown about and it stopped being fun.’ But Miranda couldn’t just give it all up and walk into the sunset.

At 48, he got on his wife’s nerves, and after spending time with his kids, there was plenty left in the tank. “I have known Luis for 20 years and he is a very high-energy person,” says Deepak Parekh, chairman of HDFC and one of Miranda’s mentors. “He has built a strong network and rarely needs an introduction to be made.” This combination could prove handy in the world of philanthropy, where there are causes aplenty but tight-fisted donors make financing difficult .

“This is a tough job for him to do,” says Parekh. “But he’s good with people and will make the right calls to get them to not only donate money but their time too.” For Parth J Shah, founder of Centre for Civil Society (CCS), Miranda’s addition as an advisor has added not only a well-versed spokesperson to the cause, but also a career networker, who is able to dive into his rolodex and persuade corporates to spend more time with these causes.

When Howard Gardner, a top professor with Harvard University, visited Mumbai earlier this year, Miranda hosted a 2,000-person get-together for him and helped evangelise CCS’ views on education and key legislations such as the Right to Education Act.

Then, when CCS wanted more members for Leaders in Education Advocacy and Policy, a consortium of nonprofit and for-profit bodies in education, he worked the phones and had PE fund Gaja Capital and Manipal Group come aboard as members. Like he did with Sneha, Miranda also restructured CCS’ finances , converting it from a not-for-profit to a sustainable enterprise, one that now does financial forecasting for three years and reports data to investors better. Miranda is finally doing what he has been threatening to do for two decades. “There is a soul to philanthropy,” he contends.

“There is a lot of passion in this sector that is not properly channelled.” The challenge for him, adds Miranda, is to channelise this energy in the right direction, only as an advisor, and not threaten project managers by getting his hands dirty with the day-to-day management of his pet projects.